I learned by chance that Jennifer Bartlett was exhibiting at Locks Gallery in Philadelphia in October. I could actually have managed to go, but as it happened I didn’t. And consequently though I have in recent years gotten very well acquainted with Bartlett’s images and ideas, I have only seen an actual painting once – at the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh.

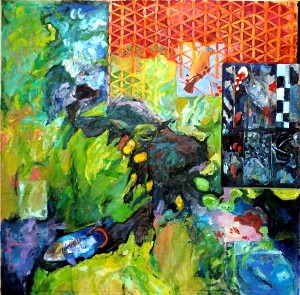

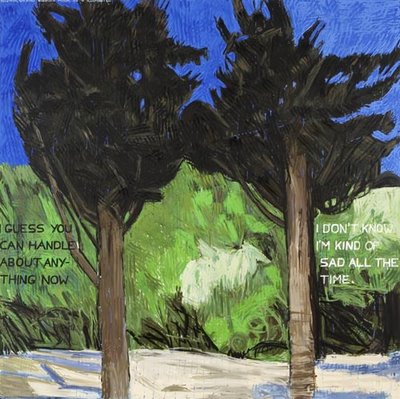

Seeing the Bartlett exhibit on line was what finally dissuaded me from making the long drive to Philly. The paintings lack the verve of her strongest pictures and seem to bow and scrape too much to a whole laundry list of clichés. So, for instance, words are stenciled over the images. One of the messages takes a crude jab at religion. The sizes of the pictures don't appear to serve any purpose other to be large for largeness sake (which is to say they lack scale) and the qualities that one really wants to respond to – the rich color, the tropical subject matter, the formal simplicity – all these things are made to take a back seat to prefabricated, off-the-shelf “edginess.” Most high end, up-scale art is now predictably McEdgy. And it makes me weary.

I never did like Jennifer Bartlett’s painting for the reasons that constituted its official virtues. For that reason, some of the pictures that interest me most are also lesser known (such as the

Up the Creek series and

To the Island works). The Matisse-indebted, lush and lyrical side of her inventiveness has always provided the attractive magic for me. Other features – like the stuck-on, outside the picture-plane objects – I find uncompelling.

At times I have wondered why I should like her work at all. Isn’t she only doing what Matisse did already, what Matisse and others had done more forcefully? And

Rhapsody for a long time struck me as more childish than child-like. Yet I found myself continually returning to her images – even when I rather strongly disliked them. Over time, I suppose they won me over. If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, every hip and trendy artist today is deeply in her debt. The ubiquitous square, the modular picture, the adoption of commercial illustrative styles for “high art,” the repeated and/or split screen images all find their roots in her early conceptualist manner. She seems to have anticipated the personal computer by a couple decades.

I did not go see her most recent show, not wanting my first acquaintance with a body of actual pictures to become a disappointing moment. I would prefer seeing her stronger works whenever I'm finally treated to my first brush with the real Mac Coy. But even knowing the images through books gives one pause at the inventive power of this charming artist. When the passage of time allows one to enjoy her work for its beauty – when we are forgiven for not caring about “edginess” any more, then Bartlett’s work will come into the foreground in a new way, and it will have to stand or fall in comparison with its antecedents. How will Bartlett’s swimming pool cherub stand its ground next to a Matisse odalisque? Time will tell.

Thinking about the Bartlett exhibit at Locks Gallery I am troubled by her decision to eschew something that might have been authentically beautiful. She could have painted her landscapes in the straightforward way that would evoke delight in the viewers. It would have put her into territory once owned by Winslow Homer.

Really modern art can, will, needs to confront the real vision of actual, present, living nature. Light -- air – atmosphere -- movement or stillness – light and dark – sky and water. These elemental things mean more than slogans stenciled over the surface. When the art is the thought in your head, one readily and gladly dispenses with politics and trends. A conceptualist ought to know that!